CPT President Mark Spivak, functioning as a research consultant in conjunction with Emory University’s Neuroscience Department, co-authored a second research paper published in the prestigious academic journal PLoS One. The article, entitled Replicability and Heterogeneity of Awake Unrestrained Canine fMRI Responses, coauthored by Dr. Greg Berns, MD, PhD, Andrew Brooks, PhD, and Mark Spivak, CPT, details an expansion and replication of the group’s first neuroscientific study that received worldwide attention for becoming the first research project that without the use of sedation or restraints successfully obtained quality fMRI images of a non-human animal.

In May 2011, Emory and CPT began collaborating on a humane approach to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to better acquire knowledge related to the human-animal bond, canine cognition, canine emotions, canine sensory perception, and canine receptive communication. Mark co-designed the initial research study, designed the selection criteria for the subject animals, and designed the training protocols, whereby he identified the key variables, then used the processes of systematic desensitization, habituation, behavior shaping, behavior chaining, and positive reinforcement to direct the training of two subject dogs to cooperatively enter the fMRI tube and coil and remain motionless for the required time period.

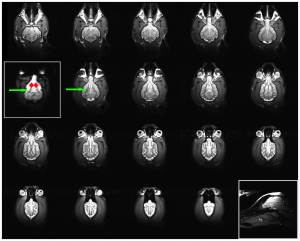

On May 11, 2012, the group published their first paper, Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs that documented the process and the cognitive findings for two dogs. The group’s second paper, published on December 4, 2013, documents the process and relevant research findings for a total of 13 dogs.

The abstract to the paper reads as follows:

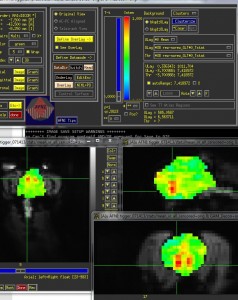

Previously, we demonstrated the possibility of fMRI in two awake and unrestrained dogs. Here, we determine the replicability and heterogeneity of these results in an additional 11 dogs for a total of 13 subjects. Based on an anatomically placed region-of-interest, we compared the caudate response to a hand signal indicating the imminent availability of a food reward to a hand signal indicating no reward. 8 of 13 dogs had a positive differential caudate response to the hand signal indicating reward. The mean differential caudate response was 0.09%, which was similar to a comparable human study. These results show that canine fMRI is reliable and can be done with minimal stress to the dogs.

For those wishing to read the entire paper, please click the link in the first paragraph.

Until the Emory/CPT research team completed their groundbreaking studies, the neuroscientific community remained doubtful whether it was possible to effectively scan non-sedated unrestrained animals, as there are a number of pertinent factors that needed to be overcome to obtain quality echo planar fMRI images. The factors included:

- A requirement that cranial motion not exceed 2 – 3 mm within any spatial plane,

- An absence of enclosure anxiety,

- An absence of anxiety to high-pitch, low-pitch, high-volume, and sudden noises,

- A tolerance to handling,

- A tolerance to wearing ear muffs, and

- Comportment amidst slippery floor substrates and unfamiliar hospital and hospital-type environments.

Prior to the Emory/CPT project, when studying animals, neuroscientists used sedation and/or restraints to maintain the static positioning of the subject, usually a primate or rodent. Sedation is acceptable for a structural MRI to scan tissue for veterinary diagnostic purposes. However, for neuroscientific purposes, sedation precludes the researchers from effectively studying cognition, as the animals are not in a normal state of alertness. Moreover, anesthesia interferes with the oxygen levels within pertinent brain tissue, which reduces the accuracy of fMRI readings that use a process called blood oxygen level dependency (BOLD). Consequently, to restrict motion while avoiding the complications presented by anesthesia, some researchers instead used mechanical restraints about the head, torso, and extremities. The restraints included pillories, stockades, metal braces, leather straps, and surgically implanted halos.

In contrast, the Emory/CPT team insisted on using only humane methodologies that studied cognition in an awake pet dog population that participated willingly and cooperatively and that remained in a normal, relaxed emotional state, rather than the anxious emotional state exhibited by the restrained laboratory animals. The study measured differences in caudate responses to two human hand-signal communications, one that meant a reward was forthcoming and the other which meant that no reward was forthcoming. The caudate, especially the nucleus accumbens/ventral striatum and to a lesser degree the left amygdala, activate with dopamine and serotonin respectively when there is anticipation of a reward, the expectation of pleasure, or the receipt of pleasure. The study demonstrated that the dogs learned to cognitively and emotionally differentiate the relevance of the two communication signals, as indicated by the significant difference in brain activation. Moreover, using the humane approach designed by the team, the scan images were very clear. Thus, the team was able to further prove to the worldwide neuroscientific community that humane approaches are viable when using fMRI as a tool to study animal cognition.

Planned future research will study canine social olfaction, vision, learning, inhibitory control, and emotions for applications that the group hopes will ultimately improve the productivity of selection and training for service dogs and military working dogs. In addition the group hopes their findings will empirically improve the industry accepted training protocols used in pet dog programs. In anticipation of continued funding, the Emory/CPT research team plans to expand in 2014 to a team of 30 trained dogs.

For more information about the Emory/CPT Neuroscience Project, please review the links contained in this article or contact Mark Spivak at CPT by email (MarkCPT@aol.com) or by phone (404-236-2150).