CPT President Mark Spivak, functioning as a research consultant in conjunction with Emory University’s Neuroscience Department, co-authored a fourth research paper published in a prestigious peer reviewed academic journal. The article, entitled “One Pair of Hands is not Like Another: Caudate BOLD Response in Dogs Depends on Signal Source and Canine Temperament,” co-authored by Dr. Peter F. Cook , PhD, Dr. Gregory Berns, MD, PhD, and Mark Spivak, CPT, describes the existence of fMRI biomarkers that may help researchers determine a dog’s suitability for a designated working role.

The fMRI biomarker technique has potentially important applications for the military and for the service dog industry. The cost to train a service dog is typically stated as anywhere from $20,000 to $50,000, depending upon the disability affecting the recipient and the cost structure of the organization training the dog. Yet, only one-third of candidate dogs graduate from top-tier service dog programs, despite the fact that the dogs often come from a homogeneous breeding population purposefully bred for a service dog role. Consequently, the true cost to prepare the average service dog is $105,000.

However, if prior to entering a training program the biomarker technique can predict future graduates and can do so with just 50% accuracy, then the true cost of training a service dog will be reduced to $70,000, a savings of $35,000 per graduated dog. Moreover, as the research team acquires further data the predictability should continue to improve, which will provide greater economies to service dog organizations, better-trained dogs for disabled citizens, and more graduating dogs for each dollar of donor contributions received by nonprofit service dog entities.

One can similarly apply the mathematical model to military explosive detection dogs, where a higher than optimal percentage of candidate dogs fail during the training process and a significant number of working dogs are released after a year or less in service. Furthermore, if an explosive detection dog is not the ideal dog for the role there is a risk to human life.

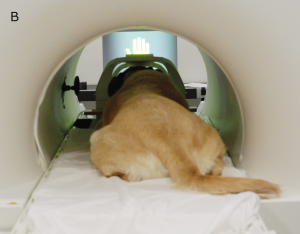

The experiment documented in the article consisted of training community dogs to take fMRIs without the use of sedation or restraints and then further training the dogs so that they would remain in the Siemens 3T scanner while receiving communications from a computer screen without any human in view. The difficulty in the training process was multifold. The dogs must climb steps, traverse a narrow walkway, maintain a down-stay for multiple 10-minute blocks within a confined enclosure, ignore high-pitched 95 dB sounds, and remain motionless throughout the process (movement of more than 2mm in any spatial plane causes unacceptable noise artefacts in the images)- and then ultimately perform the preceding without owner accompaniment.

There was one additional training novelty that the team added for this experiment. The dogs had to learn to accept treats from a mechanical device that the team coined “the treat kabob.” The kabob was a PVC tube in which laid a skewer with a hot dog. During a live scan, at specified moments the subject dogs would receive a treat from the skewer, slid up the tube to the dog’s mouth.

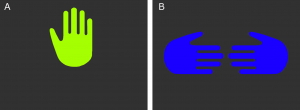

During the training process, once the dogs could remain motionless in the practice scanner and accept treats from the kabob, the research team introduced the dogs to two hand signals. One signal meant a reward was forthcoming. The second signal meant they would not receive a reward. When the dogs appeared to understand the meaning of the two hand signals the team and project volunteers next trained them to accept an illustrated colored version of the signals generated on a computer screen. The team used the color of yellow-green for the reward signal and blue for the no-reward signal, as those are the two colors that dogs can most easily discriminate.

During live scans, the dogs randomly received the reward and no reward signals in accordance with three different cases. Case 1 was the owner communicating the signals. Case 2 was a complete stranger communicating the signals while the owner was out of view. Case 3 was a computer communicating the signals while no human was in view. The dogs experienced 40 trials of each case separated into six 20-trial blocks with each case rotating in a pyramidal manner (i.e., 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 1) to remove sequence bias.

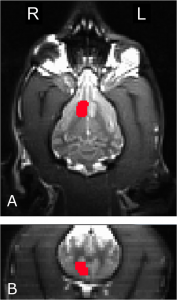

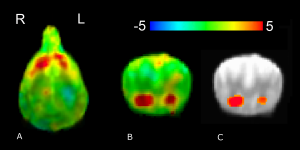

Upon accumulating data, the team analyzed the BOLD (blood oxygen level dependent) response in each dog’s caudate nucleus, an area of the brain that activates upon the commencement of the anticipation of reward. The key measurement of interest was the delta in caudate activation between the no-reward and reward states within each of the three different case states. The team then compared the fMRI results to the personality profiles of each dog as determined by the standardized C-BARQ test developed by the University of Pennsylvania. The results showed that service dogs had a much stronger response to Case 1 in comparison to other dogs and in comparison to the other states. In contrast, dogs with a history of aggressive reactivity tended to respond most significantly to Case 2, when a stranger communicated a reward signal, most likely because the dogs felt safer in the stranger state only when the person’s presence was accompanied by the reward signal and the knowledge that a treat receipt was imminent.

The results are very important to the selection of service dogs and working dogs. Service dogs must remain highly bonded to one person. Whereas a service dog must remain cordial to everyone, while working the dog may not socialize with anyone but the owner/recipient. Diametrically, the role of a therapy dog is very different and would require a different dog. A therapy dog is brought to a facility by the owner and then must principally interact with third parties. And futuristic explosive detection dogs that work independent of human accompaniment must be even more different in temperament. Such independent detection dogs may work off-leash far away from their handlers. Therefore, the dogs must remain principally motivated by the task itself, not by social communication. Moreover, they must maintain high reliability and focus even without an authority figure nearby.

The fMRI biomarker test can help to slot a dog for any of the aforementioned working roles or determine whether a dog is not highly suitable for any type of complex working participation. To use an analogy, the biomarker process is similar to a human resource test that determines working roles for prospective employees. Someone working closely with an inside project team would need to show the strongest activity for Case 1, preference for communication from familiar people. Someone in outside sales would need to show the strongest activity during Case 2, communication from a stranger. Someone destined to work alone in a lab would need to show the most significant activity in Case 3, as the employee would need to remain content with limited social contact.

Further development of the fMRI biomarker process will occur over the next two years. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has awarded a $1 million contract to Dog Star Technologies, a company co-owned by CPT President Mark Spivak, so that Dog Star may study candidate dogs from Canine Companions for Independence’s adult training program in Santa Rosa, CA. The study will use UC Berkeley’s research scanner to compare the biomarker results of the CCI candidate dogs with the actual graduation rates. The study will also evaluate a second correlate from a special vest created by Georgia Tech’s Brain Lab.

For those interested in learning more about the fMRI biomarker experiment, we invite you to read the abstract or the entire PeerJ journal article by clicking the following link: “One Pair of Hands is not Like Another: Caudate BOLD Response in Dogs Depends on Signal Source and Canine Temperament.”

For those wishing to volunteer their time and their dogs for future Emory-CPT or Dog Star studies on canine cognition, emotions, sensory perception, receptive communication, and inhibitory control, please contact Mark Spivak by email (MarkCPT@aol.com) or contact the CPT office by phone (404-236-2150).