CPT founder and Head Trainer Mark Spivak, along with Peter Cook, Ashley Prichard, and Greg Berns of the Emory Cognitive Neuroscience Lab, co-authored a paper recently published in the journal Animal Sentience. The paper, entitled “Jealousy in Dogs? Evidence from Brain Imaging,” discusses a neuroscience research study designed, conducted, and analyzed by the authors.

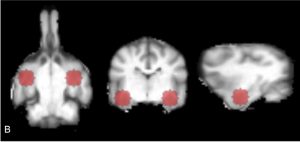

The study used noninvasive fMRI brain imaging to measure activity in the amygdala of dogs upon exposure to a human-dog social situation where the dog’s caregiver provided attention to another dog. No previous study neuroscientifically showed the exhibition of canine jealousy.

Jealousy progresses beyond envy. Whereas envy is a desire to obtain resources in the possession of another, jealousy is identified by a set of negative emotional and behavioral responses when a rival receives something one wants for oneself. Although several brain regions, including the hypothalamus and insula, may activate upon the onset of jealousy, the amygdala is the most relevant brain region.

Thirteen (13) dogs participated in the experiment. While in a Siemens 3T Trio MRI/fMRI scanner the dogs were exposed to 3 trial conditions: 1) subject dog gets food, 2) fake dog gets food, and 3) food is deposited in a bucket. Each trial began with the 7-second presentation of an object at the end of a wooden stick. There were 3 different objects. Each object cued the dog to the upcoming commencement of a specific action on the part of the owner, where the action corresponded to one of the three trial conditions. The dogs received 90 total trials, divided into 3 runs of 30 trials, where each run consisted of 30 random trial presentations.

The premise of the experiment was that if the dogs exhibited jealousy, we should observe jealousy in Condition 2, since a “rival dog” was receiving the owner’s attention and the food treat. Condition 3 was a control condition to measure the amount of activity relevant solely to the loss of owner attention and the food treat, in contrast to the loss of such to a conspecific rival. Therefore, evidence of jealousy will result when there is greater amygdala activation in Condition 2 in comparison to Condition 3.

We used a fake dog for safety and humane reasons. To provide continuity we needed to expose each subject dog to the same rival dog. However, it would be unreasonable to expect a live dog to withstand thirteen 1.5-hour MRI sessions, during which the dog had to remain in a stay position in proximal view of the subject dog for the entire duration. Moreover, should a subject dog become aggressive once jealousy was invoked, the setup would pose safety issues to both dogs and nearby humans. Thus, although the subject dogs may not be as affected by a fake dog in comparison to a live dog, the fake dog chosen looked real enough, whereupon the humane and safety issues surmounted the risk of obtaining weak data. Furthermore, during preliminary field testing outside the MRI, the majority of subject dogs behaviorally responded in a manner that indicated they believed the ceramic dog was in fact alive. When meeting the ceramic dog, the subject dogs reacted similarly to their customary behavioral response when meeting a novel live dog, barking, bowing, wagging, growling, or raising hackles, depending upon the behavioral traits of the particular subject dog.

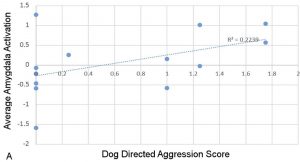

To acquire information about each subject dog’s typical dog-dog behavioral characteristics, we received C-BARQ behavioral assessments for each dog. The Canine Behavioral Assessment & Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ) is an owner-based questionnaire created at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. C-BARQ is a tool designed to provide dog owners, organizations, breeders, veterinarians, trainers, shelters, and researchers with standardized evaluations of canine temperament and behavior.

Upon the conclusion of each dog’s fMRI session, the data was pre-processed for motion correction, censoring, and normalization and then analyzed using ANTS, AFNI, and SPSS software. The results showed a significant correlation between amygdala activity and the C-BARQ dog-directed aggression score, whereby dogs with a history of aggression to conspecifics had higher amygdala activation during the initial fake dog trials. However, as the experiment progressed the dogs habituated, whereupon amygdala activity gradually diminished.

Persons wishing more information about the study should contact Mark Spivak via email (MarkCPT@aol.com) or phone (404-236-2150).

Atlanta, GA

Sandy Springs, GA

Decatur, GA